As the crude world turns: Tanker rates, sanctions, rising US exports

The latest data on booming U.S. exports, resilient Russian flows, and how sanctions impact the price of Russian crude and the cost to ship it.

The global oil trade has been transformed in the two years since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Whenever ocean trade faces an obstacle – an import ban, a price cap, a canal constraint – it reroutes around that obstacle. Cargo volumes continue to flow, like water drawn by gravity around a stone.

And whenever trade reflows due to a major event like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there are inevitably winners and losers (in shipping, usually winners).

Here’s an overview of how the war has impacted crude tanker trades, including the latest data on seaborne volumes from Kpler and the latest data on Russian crude pricing and Russian freight premiums from Argus:

US exports buoyed by European demand

U.S. crude exports are squarely in the “winner” column, enjoying heightened demand from Europe as U.S. production has increased. America has surpassed Russia to become the world’s second-largest crude exporter, after Saudi Arabia.

The EU was heavily dependent on short-haul crude imports from neighboring Russia prior to the war. Since the EU ban on Russian crude in December 2022, replacement supplies have come to Europe from both the Middle East and the U.S.

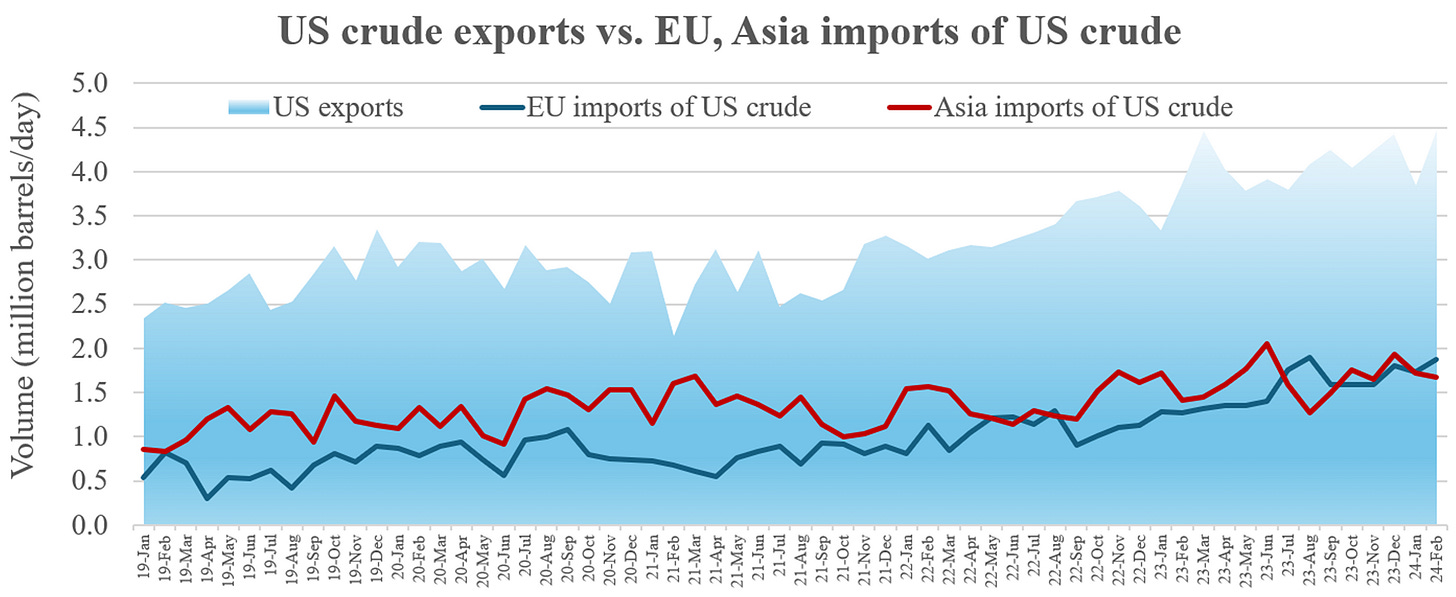

Data from commodity intelligence provider Kpler shows February U.S. seaborne crude exports (through Feb. 23) averaging 4.47 million barrels per day (b/d). If the pace persists through the end of February, it would be the highest monthly average on record.

U.S. crude exports to Europe have now edged higher than exports to Asia. Kpler data shows that European imports of U.S. crude rose by 350,000 b/d in 2023 versus 2022, with Asian imports rising 220,000 b/d. Prior to the Russia-Ukraine war, U.S. crude exports to Asia handily surpassed those to Europe.

“U.S exports have certainly accelerated over the past year,” said Reid I’Anson, senior commodity analyst at Kpler. “This is not so surprising given how strong U.S. production growth was last year, coming in way above expectations. This helped to lift all boats, albeit Europe was the biggest beneficiary.”

In the Asian market, U.S. volumes to South Korea top the list, with strong volumes also heading to Singapore and Taiwan. China and India have been major buyers in certain months, but their demand is less consistent, with these countries also taking large volumes of crude from Russia (and most of China’s crude coming from the Middle East).

The price cap and Russian crude exports

The debate continues on the impact of G-7 and EU sanctions on Russian crude exports.

If the primary focus of Western policy was to cease buying Russian exports and simultaneously protect oil markets from a sustained price surge that would negatively affect consumers, then Western actions have been a resounding success.

The first goal of the price cap was to allow Russia to transition its crude sales to new buyers following the EU import ban without creating global shortages. The price cap created a loophole that allowed U.K. and EU ship insurers and service providers to continue serving Russian export cargoes, facilitating transport.

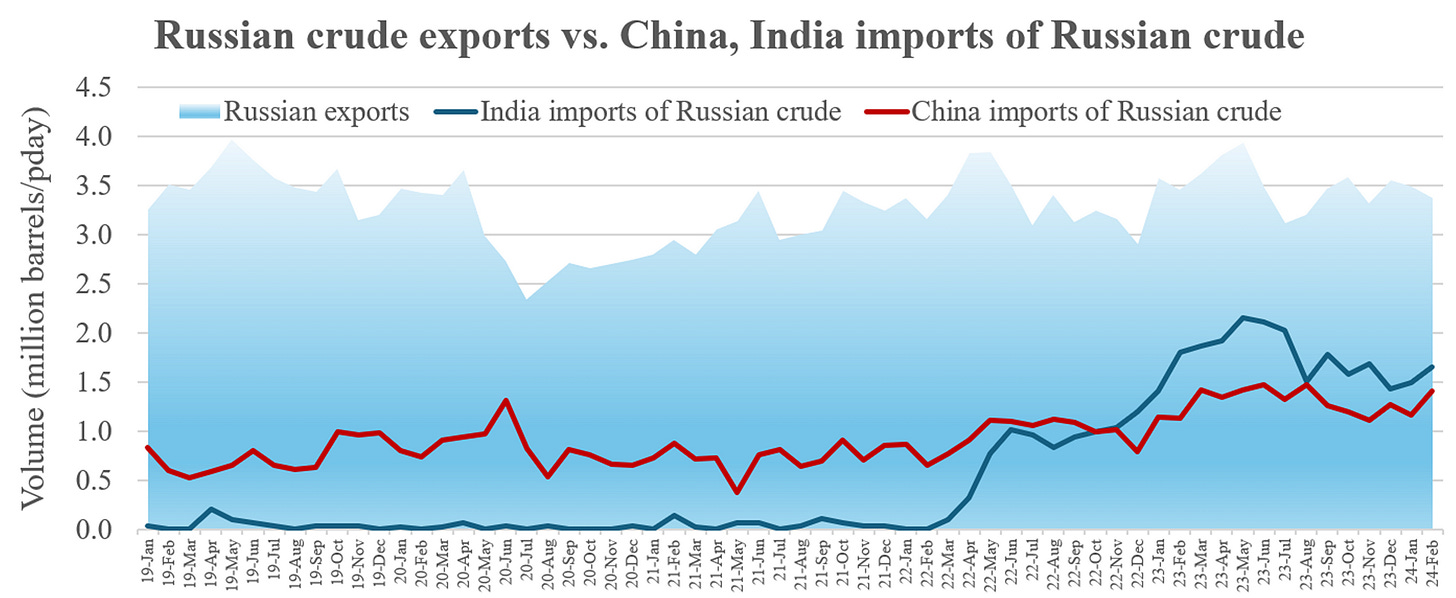

Data from Kpler confirms that Russian crude exports have remained consistently high despite the EU import ban. Russian crude exports averaged 3.38 million b/d this month through Feb. 23, up 7% from February 2022, the month the war began.

Russian crude that previously went to Europe has gone to China and India instead, with India dramatically boosting imports from Russia.

The success of the second goal of the $60-per-barrel price cap – financially penalizing Putin by forcing discounts – is more debatable, particularly given Russia’s higher export volumes.

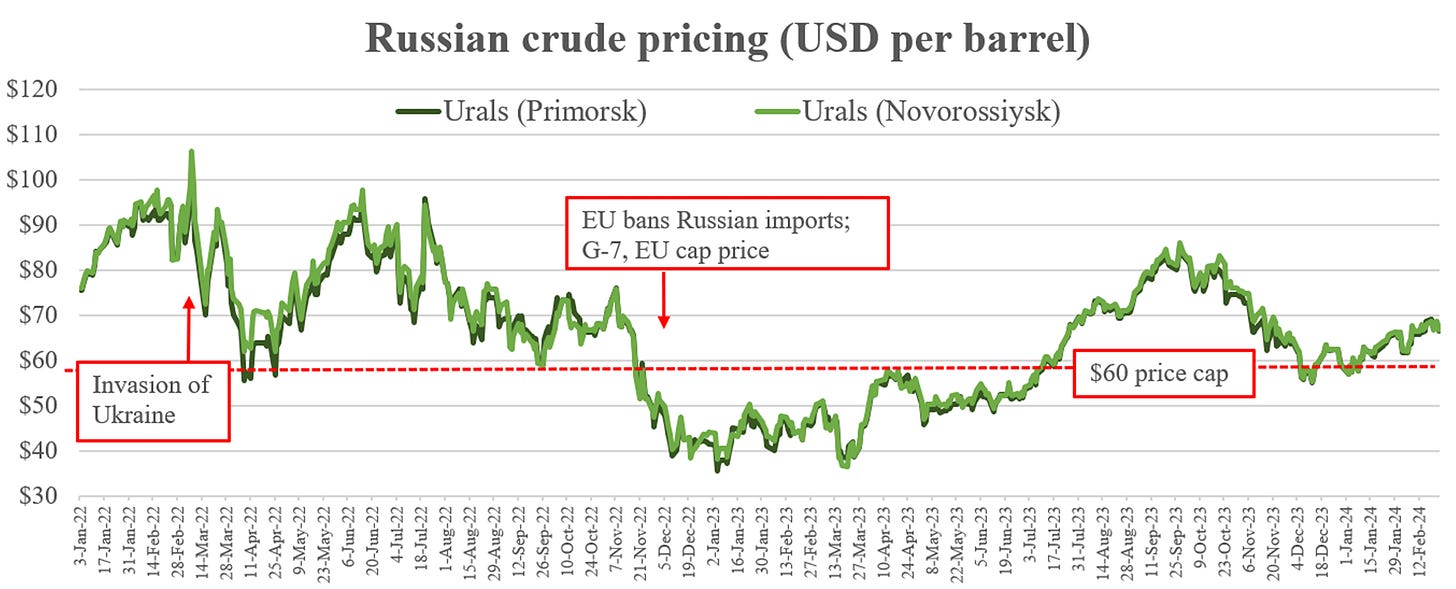

Data from Argus shows that the discount of Russian Urals (the crude grade exported from its European ports) versus Brent surged immediately following the invasion, and then again with the EU ban on Russian imports.

The initial discount was caused by “self-sanctioning” in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the second by the EU embargo on Russian crude imports, which translated into less competition for Russian crude, thus the discount – which some have argued has little to do with the price cap itself.

The winners have been China and India, which have been able to load up on cheaper energy supplies.

‘Dark fleet now reigns supreme’

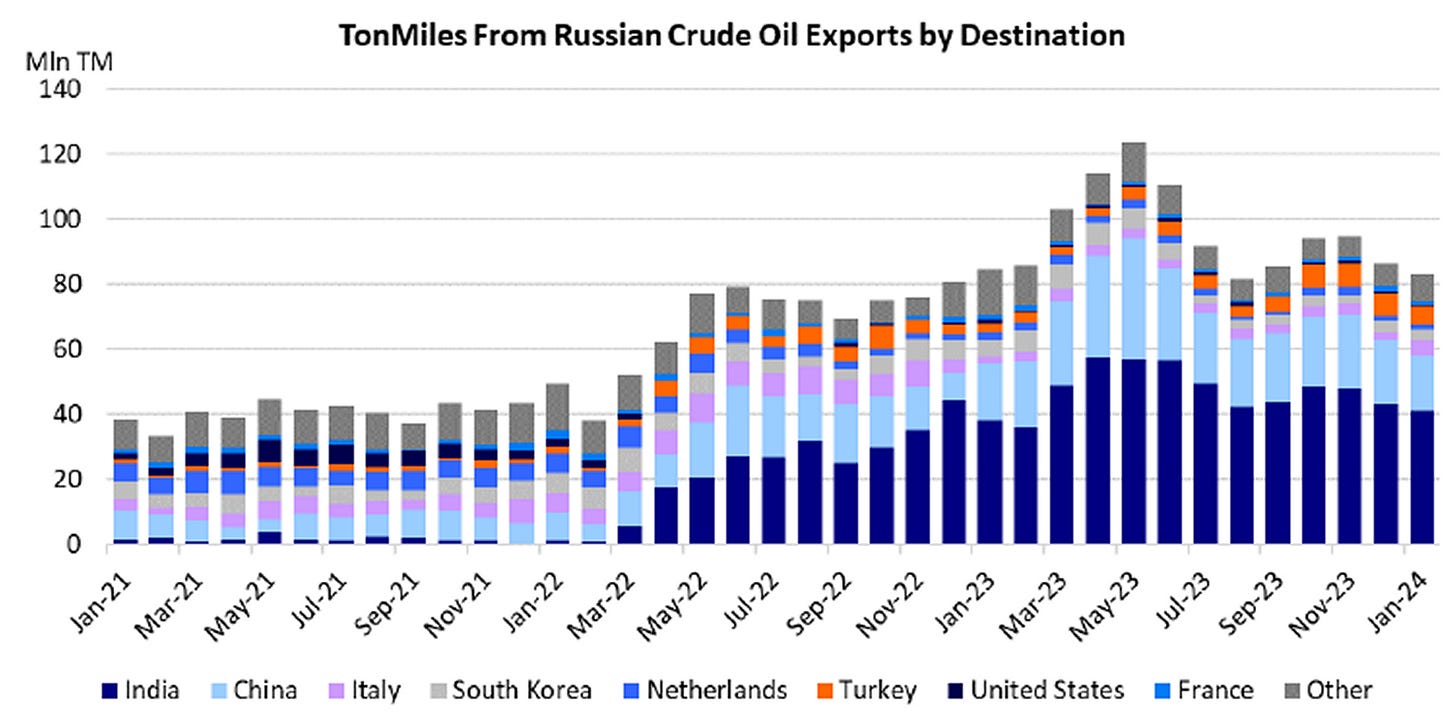

The longer distances traveled by Russian exports and EU replacement imports have increased crude tanker “ton-miles” – demand measured in terms of volume multiplied by distance. That’s a positive for rates.

That said, ton-mile upside maxed out over six months ago (see chart above) and the biggest beneficiaries of the Russian crude trade have been – and continue to be – tanker owners willing to take the risk of carrying Russian cargoes.

When Russian Urals crude was trading below the price cap, transport of Russian crude was dominated by mainstream private owners, primarily Greek owners. When Urals is above the price cap, transport is dominated by the “shadow” or “dark” fleet, comprising ships with opaque ownership that do not use Western insurance and financial services.

Data from Argus shows that Urals crude fell well below the price cap after the EU ban on Russian imports and the drop in competition for Russian cargoes, rendering the cap effectively irrelevant for the following eight months.

The price of Urals finally breached the cap in July 2023 and remained well above the cap through the second half of last year, flushing mainstream tanker owners from the Russian trade. The price has topped the cap yet again in the first two months of this year, pushing even more transport toward the dark fleet.

“The so-called dark fleet now reigns supreme over that business, while mainstream shipowners increasingly shun it, for fear of non-compliance with the G-7’s price cap,” said Alex Younevitch, global head of freight at price-reporting agency Argus.

As a result, “freight rates for Russian cargoes have become increasingly disconnected from the rest of the market. Russian-origin freight rates may often remain elevated even when the general market slows down.”

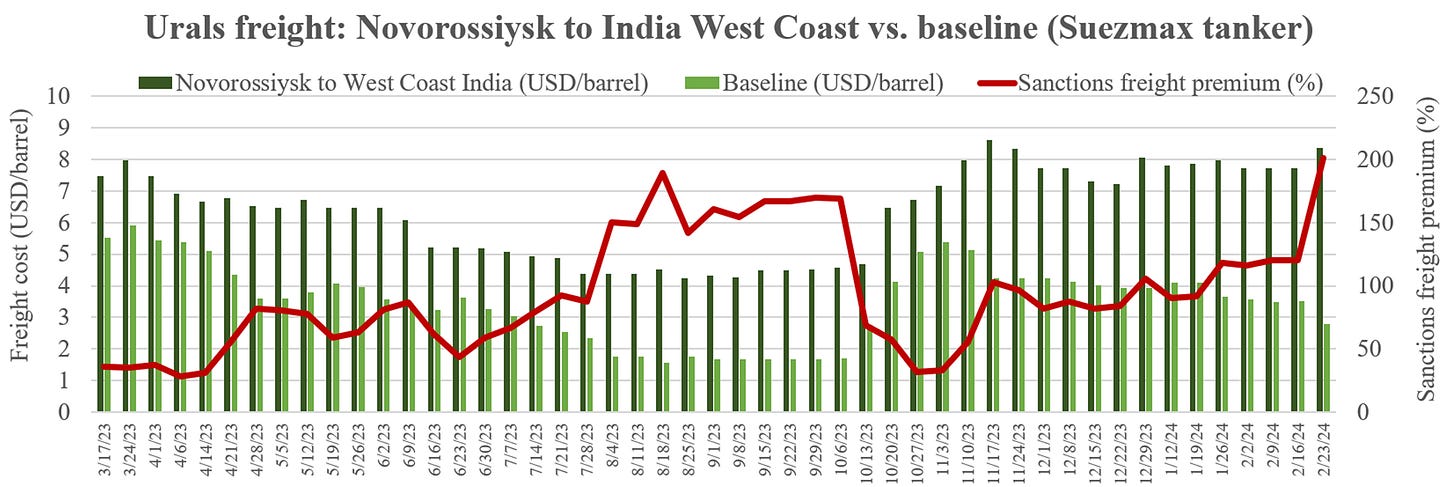

Argus assesses the cost of freight for Russian crude exports compared to a non-Russian baseline to estimate the “sanctions premium” earned by tankers carrying Russian cargoes. This data clearly shows that the sanctions premium jumps when Urals exceeds the price cap and transport shifts from mainstream owners to the dark fleet.

A few examples:

Argus calculated that freight on a 140,000-ton cargo of Urals crude shipped aboard a mid-sized Suezmax tanker from the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk to the west coast of India was $8.37 per barrel during the week ending Feb. 23. That was triple the baseline (non-Russian cargo) assessment $2.78 per barrel, equating to a whopping sanctions premium earned by dark fleet owners of 201%.

The freight cost for an 80,000-ton cargo of Urals shipped aboard a smaller-sized Aframax tanker from Novorossiysk to Northern China was 2.6 times higher than the baseline, equating to a sanctions premium of 161%.

The freight cost for a 100,000-ton cargo of Urals shipped aboard an Aframax from the Baltic Sea port of Primorsk to the west coast of India was 2.7 times higher than the baseline in the week ending Feb. 23, equating to a sanctions premium of 168%.

The next chapter: US sanctions Russia’s Sovcomflot

The question ahead for tanker and oil markets: Will increased tightening of the sanctions screws by the U.S. start to curtail Russian export volumes by reducing interest among Russia’s buyers, particularly in India?

On Feb. 23, the U.S. made its biggest sanctions move to date, putting Russian tanker company Sovcomflot and its 14 crude tankers on the “blocked” list.

According to Argus, Sovcomflot tankers have delivered 74 cargoes of Russian crude to India since January 2023, with Sovcomflot-transported cargoes accounting for 7.7% of India’s crude imports from Russia last year. India’s oil secretary, Pankaj Jain, stated earlier this month that India will not accept cargoes loaded on sanctioned vessels, reported Argus.

If sanctions tighten and force India to limit future purchases from Russia, India would presumably replace those volumes using non-Russian sources, increasing demand for mainstream tankers.

👍 Thank you for the great article