As US military polices Red Sea, US trade is nowhere in sight – it all diverted

U.S. import and export cargoes – from containers to gas to grains – are all going around the Cape of Good Hope. Have the Houthis already won?

A Hornet fighter jet taking off from the U.S.S. Dwight D. Eisenhower during Red Sea operations (Photo: U.S. Navy)

Imagine the following scenario:

The U.S. takes the initiative to use its own military assets and put its own military service members at risk to protect the commercial shipping of all nations from Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, defending the basic principle of freedom of navigation.

Despite that protection, and U.S. and U.K. military strikes on Houthi land positions, it’s still too risky for commercial shipping – the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait is very narrow and it’s not possible to stop every missile and suicide drone. For Western shipping interests, insurance costs and risks to vessels, crew, cargo and company reputations are still too high.

So, the ships divert around the Cape of Good Hope. First some segments, then all the rest.

Ultimately, all cargo to and from the U.S. and most cargo to and from other Western nations goes around the Cape. There is an initial spike in shipping rates as voyages lengthen, then rates settle at elevated but non-stratospheric levels. Ocean supply chains adjust. There is no supply chain crisis, no macro fallout.

The remaining traffic through the Red Sea is dominated by Russian export cargoes of crude oil, coal and grains, largely to India and China, and vessels ballasting back to pick up their next Russian loads; flows of energy cargoes from Mideast nations, including Iran, that are friendly to the Houthis; as well as Chinese shipping.

U.S. military forces are, by default, left to defend the Red Sea commercial shipping interests of America’s geopolitical rivals.

The Houthis effectively “win” because they successfully block Western cargo flows in retaliation for Israel’s war on Hamas.

The situation in the Red Sea is getting closer to this scenario.

Container ships, car carriers divert first, then LNG and LPG ships

Container ships and car carriers were the first to reroute. Container ships began rerouting in late November. All of the major lines had fully switched to the Cape route by the end of last year, with the exception of French carrier CMA CGM, which said it halted Red Sea transits in early February.

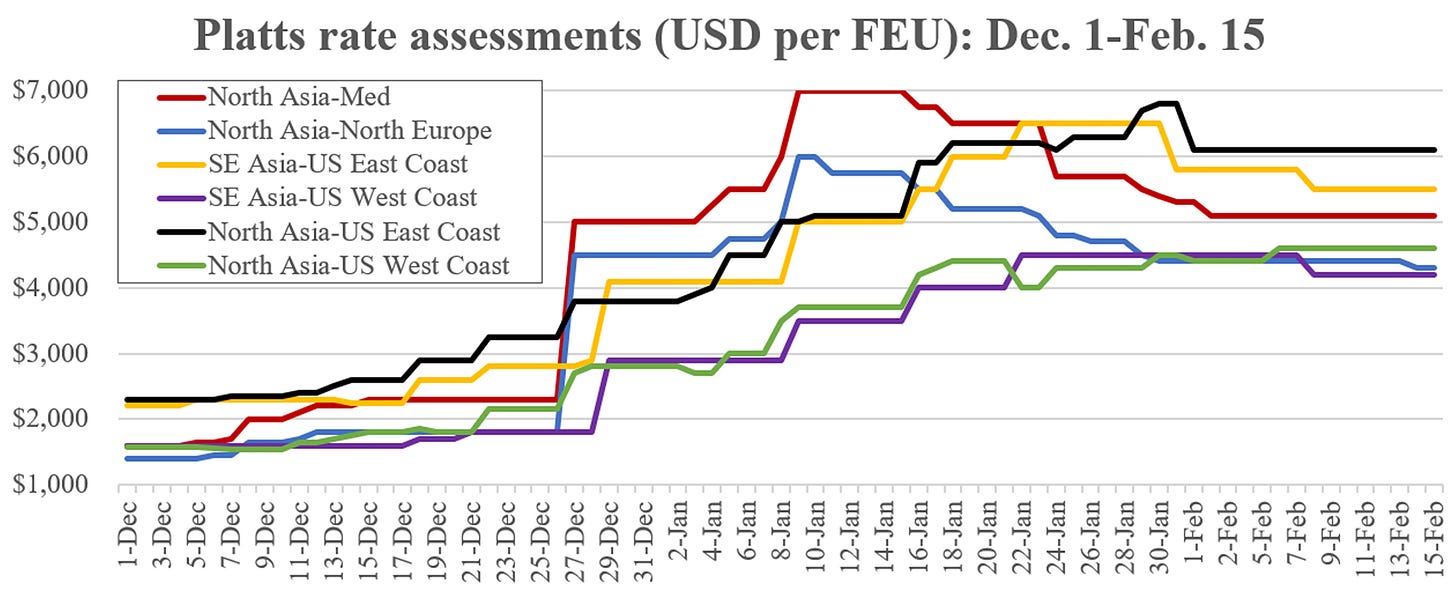

Container shipping spot rates began to rise in December as the scope of disruptions became clearer, then surged much higher through the first half of January. However, since then, Asia-U.S. spot rates have stabilized and Asia-Europe rates have pulled back.

FEU: 40-foot-equivalent unit. (Chart: Inside Shipping based on data from Platts)

Container shipping lines have increased service speed to accommodate the longer route and added ships into their service strings. The Red Sea disruption came at an opportune time for liners and their customers, coinciding with a period of vessel overcapacity and record-setting newbuilding deliveries. The disruptions required more fleet capacity, and that capacity happened to be available, or on the way.

The next vessel segments to exit the Red Sea were liquefied natural gas (LNG) carriers and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) carriers.

Prior to the Houthi attacks, high-capacity LPG tankers known as very large gas carriers (VLGCs) had diverted from the drought-constrained Panama Canal to the Suez Canal route. VLGCs on the U.S.-Asia run are now rounding the Cape instead of using the Suez.

Product carrier shift in full swing

The next mass detour to the Cape has involved product carriers – the specialized tankers that transport refined products such as diesel, gasoline and jet fuel.

As of Feb. 16, vessel-position data confirmed that product tanker traffic in the southern Red Sea had slowed to a trickle, with most Asia-Europe and Mideast-Europe flows going around the Cape. (There continue to be product tankers in the Northern Red Sea, loading at Saudi Arabian refineries for cargoes headed northbound via the Suez.)

According to data presented by Scorpio Tankers (NYSE: STNG) during a quarterly call on Feb. 14, refined product flows transiting the Suez plunged from 2.2 million barrels per day in December to 800,000 barrels per day in January to just 200,000 barrels per day in the first week of February – and this total includes cargoes moving north from Saudi Arabia that do not transit the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait.

(1) Based on speed of 12.5 knots. Number of days for one-way voyage only; (2) Data from Vortexa. (Chart: Scorpio Tankers Feb. 14 investor presentation)

The southern Red Sea “is effectively closed” to product tankers, said Scorpio President Robert Bugbee on the call.

Unlike the case of container ships, where the rerouting rate effect seems to have peaked, the effect on product tanker rates has just begun, as it takes time for longer routes to translate into less capacity available for the next round of voyage fixtures.

As Bugbee put it: “Just because you put an obstacle in the way of a group going to a bar and they have to take a longer route, it doesn’t change the number of people standing at the bar waiting for drinks to begin with. It takes a little time.”

There is another big difference between the rate effect on container shipping and product tankers: The container market was oversupplied with ships when Red Sea disruptions hit. Container shipping spot-rate upside was off loss-making levels. In contrast, the product tanker market was already tight and boasting high rates when reroutings ensued. Red Sea upside is the icing on the cake for product tankers.

“We are running the company as if the Red Sea were to open tomorrow, and on that basis, we still think that the market will be very strong,” said Bugbee.

Crude tankers: Russian cargoes remain, Western cargoes divert

Ship-position data shows that most of the vessels now transiting the southern Red Sea are crude tankers – including numerous tankers loaded with Russian crude – and dry bulk vessels.

Shipbroker Gibson said of current Red Sea tanker trades: “Vessels with significant recent Russian trading history continue to transit en masse, both laden and in ballast. The majority of conventional tonnage continues to reroute via the Cape of Good Hope (COGH).”

Outside of Russian cargoes, “most crude tankers [are] avoiding the Red Sea,” said Gibson.

While the effect on crude tanker rates “has been muted so far, if the current situation continues for any significant period of time, the impact of COGH routing will accumulate, offering support to tanker rates.”

Dry bulk ships finally diverting from Bab-el-Mandeb Strait

Dry bulk carriers transiting the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait significantly outnumber crude tankers, although bulkers carrying U.S. export cargoes are no longer plying the route. Bulkers carrying U.S. grain and coal cargoes to Asia had previously diverted from the Panama Canal to the Suez route. Now they’re taking the Cape route.

Dry bulk vessels that do transit the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait continue to be attacked, particularly bulkers with registered U.K. ownership. The Lycavitos was targeted on Feb 15. The Rubymar was hit on Feb. 18; its crew were forced to abandon ship.

Transits of bulkers owned by U.S.-listed shipowners persisted for a surprisingly long time, but those have now been halted.

Petros Pappas, CEO of Star Bulk (NASDAQ: SBLK), addressed the Red Sea situation on a conference call on Feb. 13. Two of Star Bulk’s vessels were recently attacked by the Houthis: the Star Iris (carrying Brazilian corn to Iran) on Feb. 12 and the Star Nasia on Feb. 6 (the Nasia departed from Norfolk, Virginia, and was en route to India, implying it was loaded with U.S. coal).

“We had two cases of charters where we asked our charterers not go through the Suez Canal, but legally, we could not do that, because until that time [when the charters were agreed] we did not know about the attacks on the Eagle Bulk and Genco vessels,” said Pappas.

The Genco Picardy, owned by Geno Shipping & Trading (NYSE: GNK), was struck on Jan. 17. The Gibraltar Eagle, owned by Eagle Bulk Shipping (NYSE: EGLE), was hit on Jan. 15.

“We were advised that we had to follow the charter party and send the vessels through the Suez,” said Pappas. “So, the first vessel [Star Nasia] passed and it was attacked three times. While that was happening, the second vessel was already passing through the Suez, so we couldn’t divert it. And it was attacked.

“Going forward, we will not be passing through the Suez Canal anymore, because we are obviously a target of the Houthis, being a public company registered in the U.S.”

How Red Sea crisis impacts US imports and exports

The change in trade flows since the Houthi attacks has been swift and far-reaching.

As of Feb. 16, ship-position data for all commercial vessels in the world bound for the U.S. or departing from the U.S. showed zero vessels passing through the southern Red Sea. The route transition – from a U.S. trade perspective – is now effectively complete.

U.S. supply chains have adjusted without any negative effects on the U.S. economy, despite earlier warnings to the contrary.

The specific consequences by shipping sector:

Container imports – Diversions affected Asia-U.S. East/Gulf Coast containerized cargoes that previously used the Panama Canal and had rerouted to the Suez, as well as cargoes to East/Gulf Coast ports from India and other Asian countries that traditionally use the Suez. Spot freight prices are significantly higher than before the route diversions, but not to the extent that will cause goods price inflation. Spot rates are expected to decline as the year goes on. There have been delays, but nonetheless, monthly U.S. import volumes are rising. Containerized U.S. imports rose 7.9% in January versus December, according to Descartes.

LNG and LPG exports – The U.S. is the world’s largest exporter of LNG and LPG. Diversions affected LNG and LPG cargoes to Asia that previously used the Panama Canal and had switched to the Suez. All U.S. LNG and LPG exports to Asia are now rounding the Cape. Voyage time is longer, but spot rates for both LNG and LPG ships have fallen since the Red Sea crisis began and are now below their five-year averages, according to data from Clarksons.

Crude oil exports – U.S. crude exports to Asia are loaded aboard very large crude carriers (VLCCs, tankers that carry 2 million barrels of crude), which have always used the Cape of Good Hope route, thus there is no disruption to U.S. exports. Meanwhile, the disruption of European crude imports from sources west of the Suez is a positive for American exporters: It could incentivize replacement cargoes to Europe from the U.S. Gulf.

Refined products exports – The vast majority of U.S. refined products exports head to Europe and South America and do not transit the Suez, so no disruption effect. And, as on the crude side, Red Sea disruptions to Europe’s sourcing of diesel and other refined products from west of the Suez is a plus for U.S. products exports demand, due to replacement cargo potential.

Dry bulk – The Red Sea crisis impacts U.S. grain and coal exports to Asia that first switched from the Panama Canal to the Suez Canal, and have subsequently switched to the Cape. Voyage time is longer. But overall, dry bulk freight costs are not elevated. According to Clarksons data, average spot rates for Panamax and Supramax bulkers – the vessel classes that carry U.S. grain and coal exports – are both down since the start of the Houthi attacks, and in line with the five-year average.

Well done thank you