Panama Canal added more reservations in January. It didn’t help – transits fell

Also in this issue: How the global supply chain crisis changed shipping journalism

(Photo: ACP)

The drought in Panama caused a dramatic plunge in canal transits in the second half of last year, with declines accelerating in November as the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) severely curtailed reservation slots.

Then, signs of hope: It rained more than expected at the tail end of the year, convincing the ACP to reverse course and hike daily reservation slots to 24 in January, up 9% from 22 in December.

The more reservation slots, the more transits, right?

Wrong. According to newly released data from the ACP, transits continued to decline in January. The bottom has yet to be reached.

A total of 702 commercial ships transited the canal in January, down 5.9% from December, a higher pace of sequential decline than in the prior month.

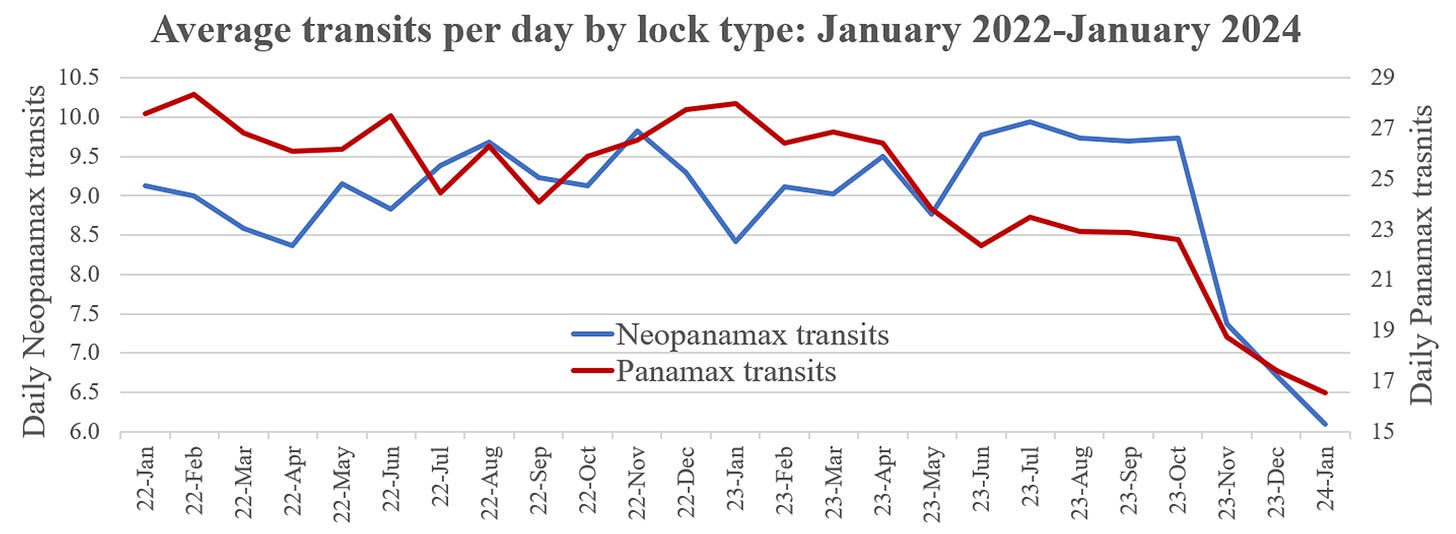

ACP stats on average daily transits highlight how severely the drought has affected canal traffic – and how the numbers are still sinking.

(Chart: Inside Shipping based on data from ACP)

There were an average of 16.55 transits per day through the smaller Panamax locks in January. The drought first began hitting the Panamax locks numbers in May 2023, with steady, ongoing losses ever since. This January’s average was down 37% from the average in April 2023, prior to the Panamax locks drop-off.

The fall in transits via the larger Neopanamax locks has been much more sudden and steep. Traffic via these locks held up through October, then collapsed.

There were an average of 6.1 Neopanamax transits per day in January. Average daily transits were down 37% in January versus October, prior to the Neopanamax drop-off.

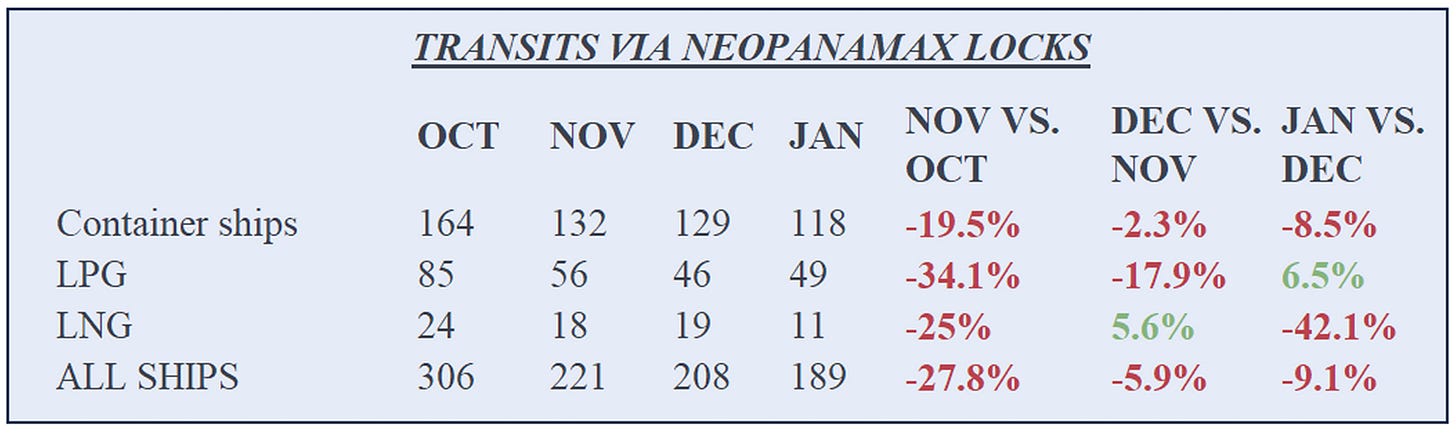

Neopanamax locks

The Neopanamax locks primarily serve larger container ships, high-volume liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) tankers known as very large gas carriers (VLGCs), and liquefied natural gas (LNG) carriers.

Neopanamax transits fell 9.1% in January versus December – a much steeper sequential decline than in the prior month – even though the number of Neopanamax reservations slots increased from six in December to seven in January.

Last month’s sequential decline was spurred by an 8.5% drop in Neopanamax container-ship transits and a 42.1% slump in LNG carrier transits.

(Chart: Inside Shipping based on data from ACP)

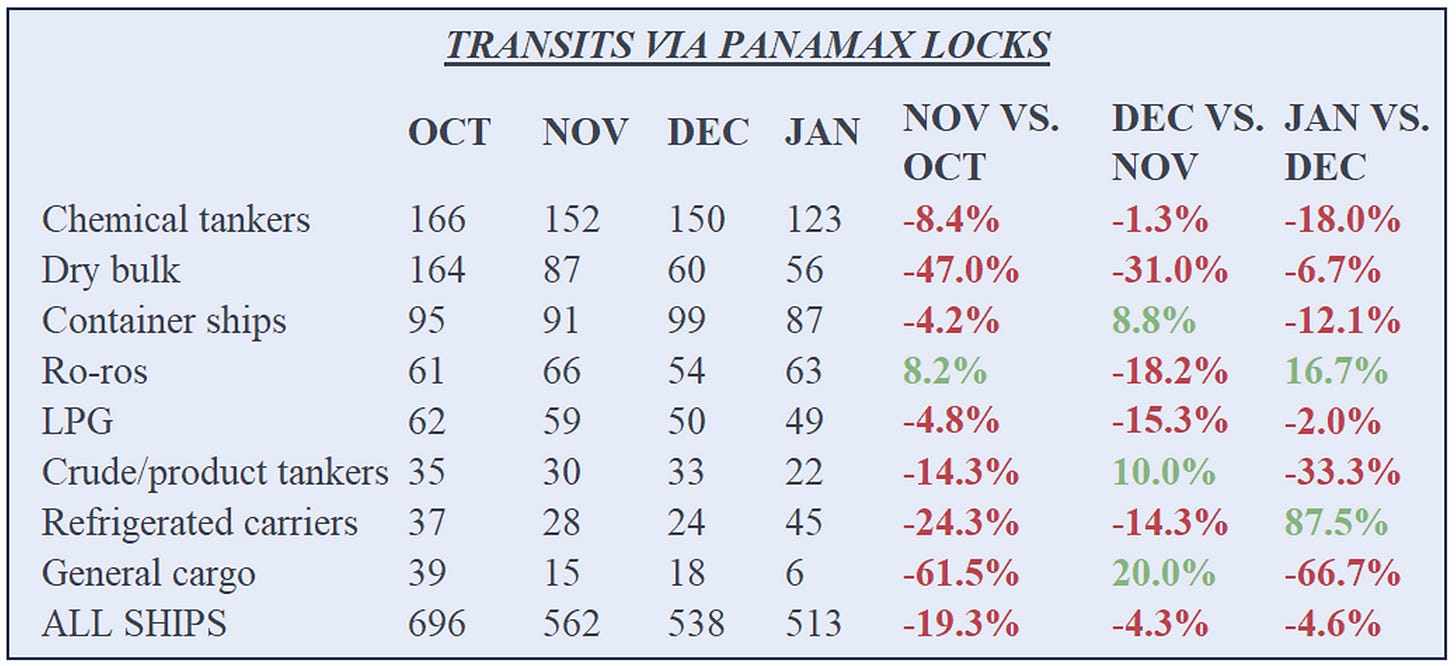

Panamax locks

Transits via the Panamax locks were down 4.6% in January versus December (much less than the Neopanamax decline), despite Panamax reservation slots increasing from 16 in December to 17 in January.

Dry bulk shipping has been the top driver of Panamax transit losses over recent months. Dry bulk transits are down 65.9% in January versus October. Bulkers full of grain loaded in the U.S. Gulf and bound for Asia have shunned the Panama Canal and rerouted via the Suez Canal or Cape of Good Hope.

(Chart: Inside Shipping based on data from ACP)

How the global supply chain crisis has changed shipping journalism coverage

In the wake of the supply chain crisis, when shipping news went mainstream, there’s more information – and more misinformation.

(Photo: Flickr)

There’s no shortage of information out there on ocean shipping. The problem is that there’s a lot more information than there used to be – and a good portion of it is biased and sensationalized.

Here’s a first-hand view on how the shipping information flow has dramatically changed since the supply chain crisis, and how those changes have created new challenges for those needing accurate information to guide their decisions.

Shipping coverage pre-supply chain crisis

Prior to the supply chain crisis, the general public had little interest in or awareness of the vast network of ships that delivered their retail products, energy and food across the seas. Most of the shipping news seen by the general public involved oil spills and oil-soaked birds. If a journalist told someone he covered shipping, the response was often: “You mean, like FedEx?”

The vast majority of shipping journalism was provided by specialized trade publications with expensive paywalls. The journalists who wrote for these publications knew the market and were overseen by editors who had years of experience covering shipping. The old-school “gatekeeper” model helped to ensure accuracy.

There were only a small number of writers in the world covering ocean shipping back then. We’d sit side by side at shipping conferences in New York, Long Beach, Athens and Oslo, and simultaneously roll our eyes when panelists assured us, yet again, that “the rate recovery is just around the corner.” We’d catch up over drinks at conference cocktail parties and express our mutual amazement at the latest antics of Greek shipowner George Economou.

The audience for shipping journalism was likewise small in that era: Our readers were primarily ship operators, cargo shippers, institutional investors and the professionals who served the industry (lawyers, bankers, insurers, etc.)

Enter the supply chain crisis

The dissemination of shipping information today is vastly different, for three main reasons: the explosion of public interest in and awareness of ocean shipping sparked by the supply chain crisis; sweeping changes in the journalism industry due to the collapse of traditional revenue models, leading to the rise of digital journalism powered by social media and Google search; and the proliferation of opinion-driven information on social media from non-journalists.

Over the past decade, the demise of traditional journalism business models has led – particularly with the rise of non-paywalled digital journalism – to a scramble for pageviews, and the increasing use of pageviews as a performance metric.

The good news is that most of the traditional paywalled shipping publications continue to exist, and there are several non-paywalled and hybrid platforms putting out quality shipping journalism.

The challenge to the shipping journalist whose job security hinges on pageviews is to nonetheless put objective, accurate journalism first and pageviews second.

It can be done. I worked at one of the old-school paywalled maritime publications for 15 years, writing for a niche audience, and then more recently, for a non-paywalled digital publication for five years, writing for a much larger audience that included the general public – and I believe my non-paywalled, high-pageview content was as objective and accurate as my earlier niche, paywalled content.

The bad news for seekers of actionable information on shipping is that the Internet is now awash in questionable shipping content and it’s harder to find accurate market information amid all the noise.

Shipping goes mainstream

The supply chain crisis was an extreme and sensational event. Eyeball-grabbing headlines on “skyrocketing” and “stratospheric” freight rates were entirely accurate and justified at that time. There were, in fact, “massive” traffic jams of ships clogging America’s port system.

The story of the supply chain crisis connected with everyday Americans. They feared that retail shelves would go bare, Christmas would be canceled and prices would spike – and they were looking for someone to blame.

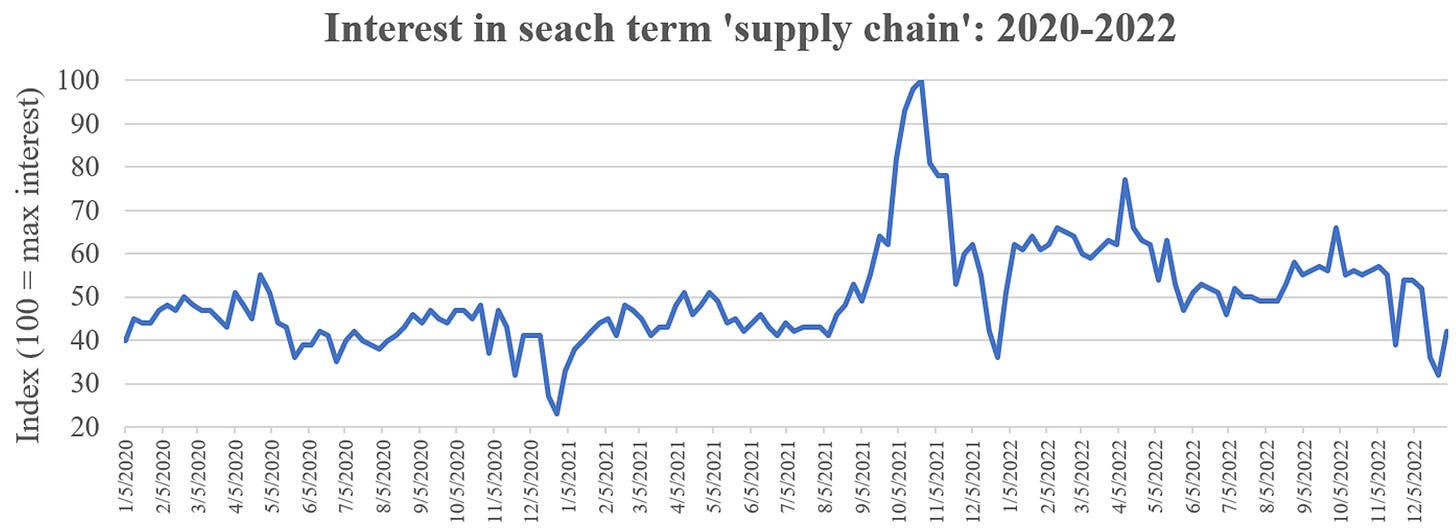

As a result, pageviews for shipping coverage surged to unprecedented heights. Google Trends data shows that interest in the search term “supply chain” rose to a historic peak in October 2021. (I had more readers for my non-paywalled stories in that single month than I did in my entire 15 years working for a paywalled media outlet.)

(Chart: Inside Shipping based on data from Google Trends)

And it wasn’t all about the pandemic-era import boom and port congestion. Public interest in ocean shipping was also boosted by the Ever Given grounding in the Suez Canal in March 2021, which coincided with the supply chain crisis.

This event became a surreal meme machine. There was everything from an Ever Given dating app to the highly popular Austin Powers parody, an Ever Given sea shanty, the “ramp” video, and endless variations on the small-digger, big-ship meme.

Shipping had officially gone mainstream.

And this attracted a whole new layer of media coverage, not from the traditional shipping journalists, but from generalists who had no prior background in ocean shipping.

‘SME’ interview pitches tied to supply chain disruptions

The surge in interest in shipping during the supply chain crisis and Ever Given grounding attracted the attention of businesses looking to use that newfound interest to promote themselves.

Many businesses, particularly tech startups focused on supply chain visibility, sought to place the quotes of their executives, acting as “subject matter experts” (SMEs), into the coverage that was suddenly garnering so many pageviews.

Public relations (PR) intermediaries pitched the availability of their client SMEs to any journalist who had published articles on the supply chain crisis. The PR reps were not from the firms that historically catered to shipping; they were mostly individual PR contractors. (At one stage of the supply chain crisis, I was receiving over a dozen pitches a day, the majority from PR reps pushing quotes from CEOs of startup companies I’d never heard of, to the point where I finally had to mark them all as spam and block the senders.)

Veteran ocean shipping journalists are very particular about who they interview for quotes, but writers who are green to the field cannot tell a legitimate shipping SME from someone attempting to use a news hook for brand exposure.

For a non-paywalled journalist who is focused on pageviews first and accurate, objective journalism second, the new ecosystem was mutually beneficial. The SME interview pitched by the PR contractor provided eyeball-grabbing quotes, the article got pageviews, the writer kept his or her job, the PR rep got paid and the SME’s company got brand publicity.

Coverage of Panama Canal, Houthi attacks

The point is: The supply chain crisis is now long gone, but this model of ocean shipping content creation is still very much alive. Each time a new shipping disruption emerges, the PR pitches ramp up again.

One example: the drought in Panama curtailing canal traffic. The Panama Canal Authority began warning of fallout in summer 2023, although transits of larger container ships in the Asia-U.S. trade were not curtailed until November. Traffic has continued to decline through this January.

But supply chains are flexible and trade has reflowed around the Panama Canal disruption. Canal restrictions have not caused a supply chain crisis. U.S. imports through January have actually risen as canal transits have fallen.

You wouldn’t know this from the PR pitches sent to me in August. They highlighted “how the Panama Canal jam is putting cargo at risk,” the “looming potential shortages as the Panama Canal restrictions impact holiday stocks,” how “the historic drought is set to disrupt global supply chains” and “how clogged supply chains could ruin this holiday season.”

A more recent example: the Houthi attacks on ships transiting the Red Sea that caused vessels to detour around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope starting in late 2023 and continuing this year.

Cue the PR pitches in my inbox: “A domino effect on world trade is expected,” “Chaos in the Red Sea is rising,” attacks have raised “extreme concern for the flow of oil, food, grain and consumer goods,” the crisis will lead to “measurable costs to the consumer and supply chain,” diversions have “taken a hard toll on shippers globally,” “this is just the latest major disruption that supply chains have experienced and [our client] can speak … to what enterprises can do to mitigate shipping concerns and continued disruptions that threaten companies’ bottom lines.”

And yet, on Feb. 8, Vincent Clerc, CEO of Maersk, the world’s second largest container liner operator, reported: “We see no sign of congestion or bottlenecks or shifts in demand. The global supply chain remains fluid.”

Looking for the next crisis to cover

The PR machine is only part of the problem. Another is that pageviews can be addictive (and provide job security) and some journalists may miss the readership they enjoyed during the supply chain crisis.

Just as the Trump presidency was a boon for The New York Times and Washington Post, the supply chain crisis was an unusually strong period for maritime journalism.

It is only natural for journalists coming off such a period of story bounty to scan the horizon for the next crisis, and, swayed by recency bias, to look at each disruption (Ukraine/Russia war, Panama Canal drought, Houthi attacks) through the lens of what occurred during the pandemic.

The journalistic risk is that a yearning for the next supply chain crisis can lead to a tone of coverage that does not reflect market realities, which may actually warrant a less exciting story with a less punchy headline read by fewer people.

Social media and shipping stocks

Meanwhile, recent years have also seen a surge in shipping information (as well as misinformation and disinformation) from another source: non-journalists betting on shipping stocks and posting on social media.

Shipping equities rose to prominence in 2004-2008 during a supercycle created by China’s ascension in world trade. Interest in shipping stocks fell after the global financial crisis in 2009 and remained weak during the following decade.

Then came the pandemic and the rise of the retail shipping investor.

Lockdowns left people at home, sitting at their computers and trading stocks. The initial interest in shipping equities during the pandemic was in tanker stocks, particularly Nordic American Tankers (NYSE: NAT), driven by the “floating storage” thesis (which turned out to be wrong).

Retail investors then switched to container shipping stocks, including container-ship lessor Danaos (NYSE: DAC) and, following its January 2021 IPO, Israeli liner operator Zim (NYSE: ZIM). Fortunes were made by investors smart enough to get out of these two names at the top.

With the rebound in retail interest in shipping stocks, social media is now flush with opinions on how world events will affect shipping rates and thus equity pricing.

It is a rule of thumb in ocean shipping that wars, disasters and other disruptions are positive for freight rates because they create fleet inefficiencies. Thus, it should come as no surprise that shareholders who want the price of their own shipping stocks to rise will highlight the most sensational, extreme scenario for any shipping disruption when they post on social media.

There’s nothing to say that people talking their own book on stocks are wrong, but when people putting out shipping information are talking their own book on stocks, it inherently raises the question: Are you getting accurate information? What is the motivation behind this post? (And there’s an interesting parallel here: Shipping disruptions are not just positive for shipping stock investor returns, they’re positive, as previously noted, for shipping journalists’ job security.)

Accurate coverage more important than ever

Add it all up and it’s easier than ever to be led astray – at the very time when objective, accurate and actionable information on ocean shipping is becoming more important.

The countries of the world played nice with each other for the first two decades of the 21st century, to their mutual benefit. No longer.

There are wars in Europe and the Middle East, and the potential for future conflicts in Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula and Guyana. There are ongoing trade tensions between the U.S. and China. Donald Trump – who’s touting a 60% tariff on all Chinese goods and badmouthing NATO – is leading in the polls.

The greater the geopolitical unrest and splintering of global trade, the more that ship operators, cargo interests and shipping investors will need accurate information on how disruptions affect freight rates and trade flows, and the more that generalist macro investors and inflation watchers will look to ocean shipping for signals on global trade flows and goods pricing.

So, the need for the right information is there, and growing. It’s just a matter of knowing where to find the right information.

Great write up, thanks.